Trending Now

- 1KOSPI

8

- 2Hollywood

8

- 3KOSDAQ

7

- 4shutdown

-2

- 5Bitcoin

-1

- 6ETF

4

- 7Mastercard

3

- 8dollar

2

- 9Ethereum

1

- 10stablecoin

Money is undoubtedly one of humanity's greatest inventions. Like the invention of writing or the wheel, money has been a fundamental driving force in the development of human civilization. Yet despite using money every day, we rarely contemplate its essential nature. To understand what cryptocurrencies and Ripple are, why they're important, and what they might mean for our future, we first need to understand what money is and how it has evolved.

Historically, the form and function of money have continuously transformed and expanded through new discoveries and inventions. Assuming that money will maintain only its current form and function is deeply ahistorical.

Money is more than just a tool for exchange—it's a social agreement. To understand how a piece of paper can hold such great value, or why the numbers in our bank accounts can determine our survival, we must first understand the essential nature of money.

Humanity's first trading method was barter. Hunters exchanged meat for farmers' grain, and fishermen traded fish for potters' vessels. But this system had a fatal limitation: the "double coincidence of wants" problem.

Consider a scenario where a farmer with rice wants meat, a hunter with meat wants a pot, and a potter with pots wants rice. How can they complete their transactions? A complex situation arises where all three must gather simultaneously to trade. As the number of trading partners increases, this problem becomes exponentially more complex.

The emergence of money solved this problem. With a common medium of exchange that everyone accepted, complex trades became simplified. Farmers could sell rice for money, then use that money to freely buy the desired amount of meat and pots whenever they wanted.

Money serves three core functions. First, it acts as a medium of exchange—a common means of payment accepted by all. We use money to exchange values based on the social agreement that a particular currency functions as a medium of exchange.

Second, money serves as a store of value, allowing us to use today's earnings tomorrow or in the distant future. This important function enables the transfer of current purchasing power to the future. Farmers can store harvest season proceeds as money and use it when needed.

Michael Saylor, CEO of MicroStrategy, has acquired approximately 450,000 Bitcoin. He argues that most of the world's wealth exists as a store of value rather than a medium of exchange, and Bitcoin — with its limited supply and secure nature - represents the perfect store of value. (Source: Yahoo Finance)

Third, money functions as a measure of value, enabling us to measure and compare the value of all goods and services. If an apple costs 1,000 won and a pear costs 2,000 won, we can easily understand that a pear is worth twice as much as an apple.

Will the functions of money forever stop at three? As civilization advances and new technologies emerge, isn't it possible for money to develop a fourth face?

For money to function properly, the trust of society's members is essential. This trust operates on three levels. First is trust in value stability—the belief that what 10,000 won can buy today, it can also buy tomorrow.

Second is trust in acceptability—the certainty that others will accept this money. This represents a kind of social contract, and for legal tender, it's enforced by law.

Third is trust in the issuing authority. Modern fiat currencies are issued exclusively by central banks. Therefore, trust that the central bank will properly manage the currency's value is crucial.

This trust doesn't form overnight. It's supported by experience and institutional mechanisms built over time. However, when this trust collapses, the effects are devastating. During Germany's hyperinflation of 1923, currency values plummeted so severely that people had to carry money in wheelbarrows. People rushed to spend their wages immediately after receiving them, as the value of money could halve within just a few hours.

Humanity's first currencies were commodities with practical value. Salt is a prime example. The Latin word for salary, "salarium," originated from "salt," as Roman soldiers received part of their pay in salt. Salt served naturally as money because it preserved well and was universally needed.

Seashells were also widely used as currency. Cowrie shells in particular were used as money for centuries across Africa, Asia, and Pacific islands because they were uniform in size, portable, and difficult to counterfeit. China used cowrie shells as currency from around 1500 BCE, which later influenced the Chinese currency's hieroglyphics.

The Chinese Shang Dynasty (17th-11th century BC) used cowrie shells as currency. The pictograph based on the shape of these shells is the origin of the character for 'shell' (貝).

The emergence of metal currency marked a major turning point in monetary history. Around 600 BCE, the Kingdom of Lydia introduced the first minted coins. These coins, made from gold and silver alloy and bearing the king's emblem, guaranteed official value. Moreover, metals had the advantages of being non-perishable, easy to divide and transport, and stable in value.

Importantly, metal currency enabled "standardized value." While commodity money could vary in value depending on quality or condition, standardized metal currency guaranteed consistent value. Consequently, trust and acceptability of money increased, minimizing the need for additional quality checks or negotiations between trading parties and significantly reducing transaction costs.

The widespread adoption of metal currency also created new problems—counterfeiting and debasement. People often sought unfair gains by mixing in lower-purity metals or shaving the edges of coins. Various technical innovations were developed to prevent this, such as milling the edges of coins.

Rulers often manipulated currency values to resolve financial difficulties. In the Roman Empire, the silver content of the denarius coin dropped from 95% to 5% between the 1st and 3rd centuries. This is recorded as one of the world's first cases of inflation.

Banknotes emerged to overcome the limitations of metal currency, beginning in 13th-century Italian city-states. Deposit certificates given to merchants who deposited gold in banks began circulating as currency. These certificates served as claims to the gold deposited in banks.

Early banknotes maintained a 100% gold reserve ratio. That is, all issued deposit certificates could be exchanged for gold or silver of equal value at any time. But bankers soon discovered an important fact: depositors rarely came to retrieve their gold simultaneously. This led to the development of fractional reserve banking, which became the foundation of the modern banking system.

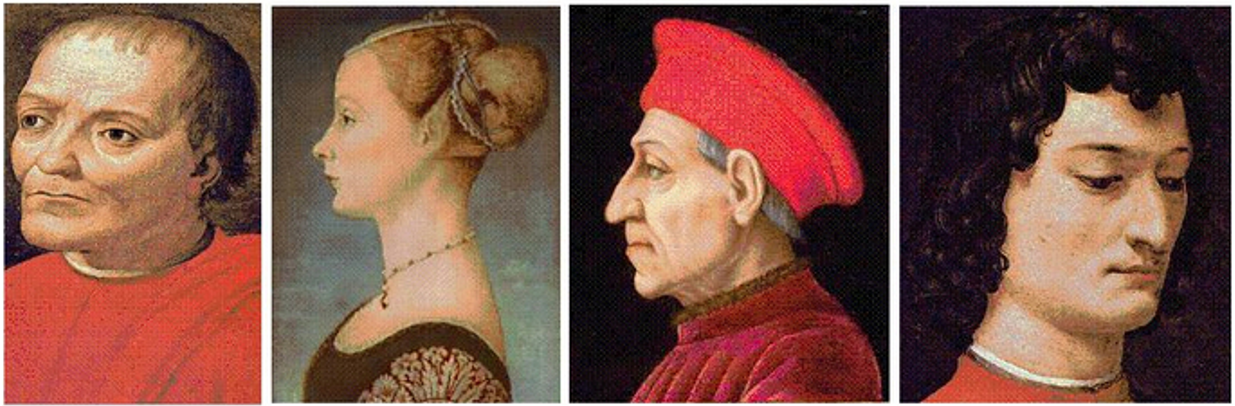

Giovanni de' Medici (left) built medieval Europe's largest financial empire and introduced innovative double-entry bookkeeping and bill of exchange systems. The Medici family used their immense wealth from finance to sponsor the Renaissance. (Source: Uffizi Galleries)

The Medici Bank exemplifies this innovation. In the 15th century, the Medici family had branches throughout Europe, centered in Florence. Letters of credit issued by one branch could be cashed at another—becoming the prototype for today's international financial system.

Credit money brought revolutionary developments in finance but also created new risks. If banks issued too much credit money or if depositors simultaneously tried to withdraw their deposits, the entire system could collapse. To address these issues, central banks became necessary.

The Bank of England, established in 1694, was the first modern central bank. Originally established to fund King William III's war efforts, it gradually assumed the role of "banker's bank." The Bank of England received monopolistic currency issuance rights from the government and managed other banks' reserves.

In the 19th century, the gold standard became the global standard. Under the gold standard, each country's currency could be exchanged for a specific amount of gold. This provided stability for international trade and financial transactions. London was the center of this system, and the British pound became the world's reserve currency.

The advantages of the gold standard were clear. Exchange rates were fixed based on gold, reducing uncertainty in international transactions. Additionally, countries could not issue currency indiscriminately, which helped maintain price stability. The period from 1870 to 1914 saw such active international trade and capital movement that it's called the "First Globalization."

However, the gold standard faced a major crisis with World War I. To fund war expenses, countries suspended convertibility to gold and issued large amounts of paper money. Attempts to return to the gold standard after the war ultimately collapsed with the Great Depression of 1929. Britain abandoned the gold standard in 1931, and the US followed in 1933.

In 1944, as World War II was ending, the Allied nations gathered in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, to discuss a new international monetary system. The resulting Bretton Woods system established the US dollar at a fixed rate of $35 per ounce of gold, with other currencies pegged to the dollar.

After winning World War II, the United States established a global monetary system with the dollar as the reserve currency. Subsequently, the world economy operated under a free trade system based on American military and economic power. (Source: Federal Reserve History)

On August 15, 1971, President Nixon announced the suspension of dollar convertibility to gold—the "Nixon Shock." Facing massive fiscal deficits from the Vietnam War, the US had printed large amounts of money. When France, observing this, demanded gold conversion and other countries showed similar movements, the US suspended gold convertibility, effectively ending the Bretton Woods system.

Thus, the world entered the era of full fiat currency. No longer was there a physical asset (gold) backing currency value; only the credit of governments and central banks sustained it.

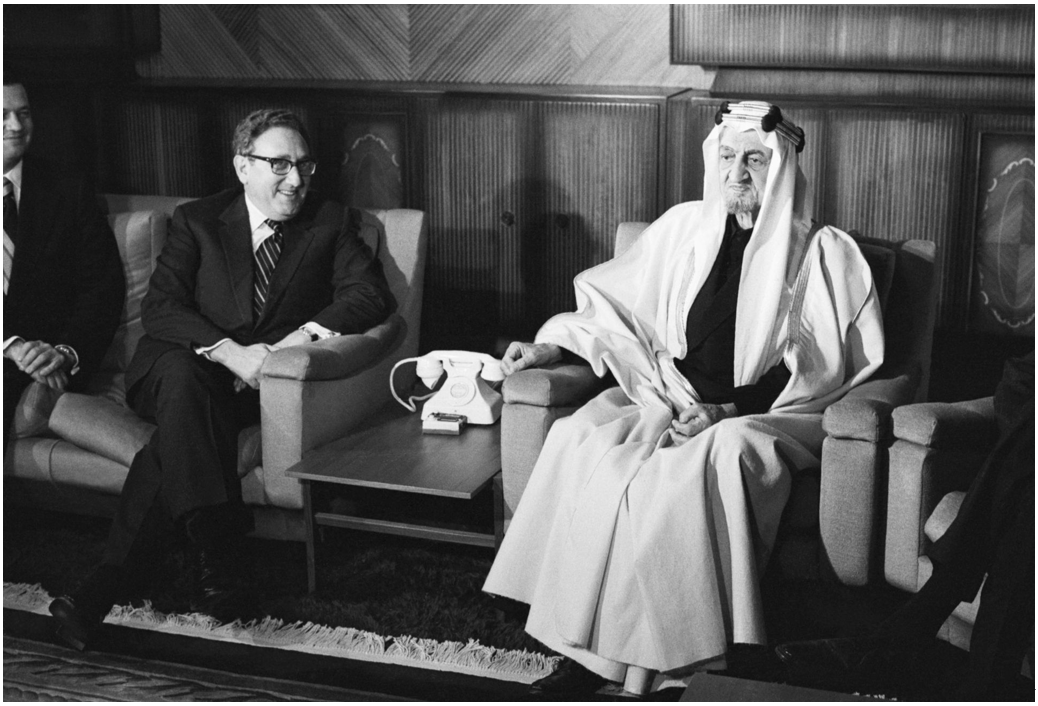

When the dollar faltered following the 'Nixon Shock', the US established the petrodollar agreement with Saudi Arabia where Saudi Arabia would settle oil transactions exclusively in dollars, while the US would guarantee Saudi security. Some claim this agreement expired in 2024, but American diplomatic experts are denying it. (Source: Library of Congress)

Interestingly, the dollar's status as the world's reserve currency actually strengthened. The "petrodollar" system, which began with an agreement between the US and Saudi Arabia in 1974, became the new foundation for dollar hegemony. With all global oil transactions conducted in dollars, every country needed dollars.

On September 15, 2008, Lehman Brothers, with its 158-year history, filed for bankruptcy protection. The collapse of America's fourth-largest investment bank plunged global financial markets into fear. Stock prices plummeted, and financial institutions began to distrust each other. Tens of trillions of dollars in asset value evaporated overnight.

The 2008 global financial crisis, which originated from Wall Street's greed, is viewed as a pivotal event that fractured the US-centered globalization trend and dollar-based reserve currency system, ultimately serving as the catalyst for the formation of a new Cold War framework. (Source: Guardians)

Even more shocking was the speed of contagion. Problems with mortgage-backed securities in the US instantly paralyzed the global financial system. Countries like Ireland, Iceland, and Greece faced sovereign debt crises. The real economy also took a severe hit, with the world economy experiencing its worst recession since the Great Depression.

This crisis starkly revealed the structural vulnerabilities of the modern financial system. The problem of "Too Big to Fail" came under scrutiny—financial institutions had grown so large that their failure could bring down the entire economy, forcing governments to provide bailouts.

The problem is that these structural vulnerabilities remain fundamentally unresolved even after the financial crisis. Rather, large financial institutions have grown even larger. JPMorgan Chase, at the center of the "Too Big to Fail" controversy in 2008, has more than doubled its assets to nearly $4 trillion by 2025. The risk exposure of systemically important financial institutions (SIFIs) continues to increase.

More seriously, the interconnectedness of financial markets has strengthened. The derivatives market has steadily grown since the 2008 crisis, with nominal trading volume exceeding $700 trillion as of 2023—more than seven times the global GDP. In such a complexly intertwined system, one institution's problem can instantly spread to become a crisis for the entire system.

After the 2008 financial crisis, central banks implemented unprecedented policies. The US Federal Reserve lowered interest rates to virtually 0% and began large-scale asset purchases called quantitative easing. The Fed's total assets grew from $870 billion in 2008 to $9 trillion in 2022. The European Central Bank (ECB) and Bank of Japan (BOJ) implemented similar policies.

These unconventional monetary policies succeeded in preventing financial system collapse but had unexpected side effects. Most serious was asset price bubbles. Stock and real estate markets surged regardless of real economic growth. The S&P 500 index rose more than sixfold from its March 2009 low to the end of 2021.

This also exacerbated wealth inequality. Those who owned assets benefited from asset price increases, while those who didn't saw their real purchasing power decline. In the US, the share of financial assets held by the top 1% increased from 23% in 2008 to 32% in 2021.

Another problem was the increase in "zombie companies." In the ultra-low interest rate environment, even low-profitability companies could easily raise funds, allowing companies that should have exited the market to survive. The proportion of zombie companies in OECD countries increased from 4% in 2008 to 15% in 2020.

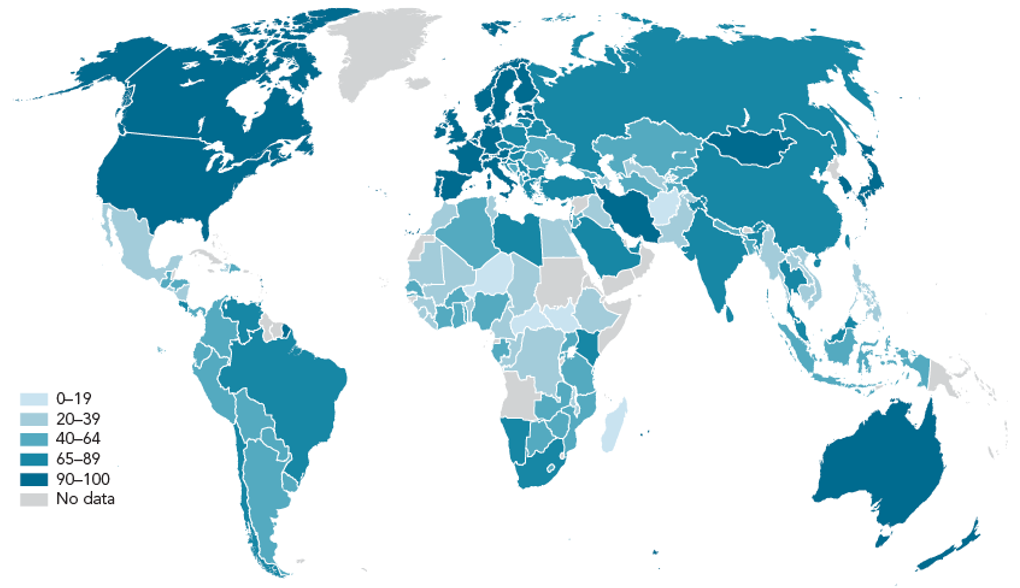

One of the biggest flaws in the modern financial system is the issue of financial inclusion. According to the World Bank's Financial Inclusion Index (FINDEX), about 1.4 billion adults, or 24% of the global adult population, still live without basic banking services. This isn't just a matter of inconvenience. Exclusion from financial services creates a vicious cycle of poverty.

Percentage of population with personal bank accounts by continent. Financial inclusion challenges, particularly in the Third World, remain an unsolved problem of modern financial systems, requiring solutions through new technologies and systems such as blockchain. (Source: World Bank)

Not having a bank account means more than having nowhere to store money. It means being unable to get loans, purchase insurance, or make remittances easily. Even if you earn wages, you must receive them in cash, and sending money to family abroad incurs high fees. Starting a business or saving for children's education becomes almost impossible.

In 2025, it still takes 3-5 days to send money from one country to another. This is because the SWIFT (Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication) system, built in the 1970s, remains the foundation of international finance. This is like using fax machines in an age when real-time communication is possible via email.

Cost is also a major issue. According to World Bank data, the average fee for sending $200 internationally is $12 (6%). For remittances to Africa or Pacific island nations, the fee rate often exceeds 10%. Given that the global remittance market is worth $700 billion annually, more than $40 billion is wasted on fees alone.

Cash is disappearing. As of 2023, cash transactions in Sweden account for less than 2% of all transactions. South Korea shows a similar trend. The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated this change. Cards and mobile payments have become everyday norms instead of cash.

However, the transition to a cashless society doesn't solve all problems. Rather, new issues are emerging. If digital payment systems fail, the entire economy could grind to a halt. In 2021, Coop, a major supermarket chain in Sweden, had to suspend operations at over 800 stores nationwide for up to five days due to an electronic payment system failure. This incident exposed the vulnerability of digital payment systems and highlighted the risks of a cashless society.

Amid these changes, central banks are hastening to introduce CBDCs (Central Bank Digital Currencies). As of September 2024, more than 134 countries worldwide are researching CBDCs, with 44 in advanced development stages. Countries like China, the Bahamas, and Nigeria have already introduced CBDCs.

A CBDC is the digital version of fiat currency. It has high stability because it's directly issued and guaranteed by the central bank. It's also programmable, allowing various applications. For example, government subsidies can be restricted to specific uses or given expiration dates.

An actual payment using China's CBDC, the digital yuan. Under its strategy to develop the digital yuan into a digital reserve currency, China introduced the digital yuan outside the mainland for the first time in Hong Kong in 2024. (Source: JD.com)

But CBDCs also have limitations. The biggest issue is privacy. Since all transactions are recorded at the central bank, the government can perfectly track citizens' economic activities. Concerns that China's digital yuan could become a "tool of surveillance" arise from this.

Thus, the modern financial system faces several fundamental limitations. Centralized control, high costs, slow processing speeds, and financial exclusion require new approaches based on new technologies and mechanisms. In particular, the following innovations are needed:

First, a decentralized trust system is necessary. As the 2008 financial crisis showed, blind trust in centralized institutions is dangerous. A new form of trust mechanism is needed to prepare for the failure of central banks or large financial institutions.

Second, efficient cross-border remittances and settlements must be possible. In a globalized world, high barriers between countries are anachronistic. Value should be transferable anywhere in the world within seconds at minimal cost.

Third, programmable money is needed. Smart money that can be programmed with specific conditions and rules beyond simple value transfer is emerging. This could completely change how we experience economic activities.

Fourth, true financial inclusion must be realized. A new approach is needed to include the 1.4 billion financially excluded people worldwide. Anyone with a smartphone should be able to access financial services.

The technological foundation enabling these innovations is blockchain. In the next chapter, we'll examine how blockchain technology works and why it could be the future of finance.