Trending Now

- 1KOSPI

8

- 2Hollywood

8

- 3KOSDAQ

7

- 4shutdown

-2

- 5Bitcoin

-1

- 6ETF

4

- 7Mastercard

3

- 8dollar

2

- 9Ethereum

1

- 10stablecoin

by COMU Research

2025-05-02 14:29:23

The 17th-century Dutch "Tulip Mania" is often cited as the world's first speculative bubble. Popular tales say that "people went mad and sold their homes just to buy tulip bulbs", but when we examine historical records, it becomes clear that such stories are exaggerated and often misunderstood. In this blog report, we'll dive into lesser-known facts and debunk common misconceptions about the Tulip Mania. The tone will remain accessible for general readers, and we’ll also include historical illustrations, documents, and charts to aid understanding.

One of the most expensive tulips traded during the mania was the 'Viceroy' variety. Records from 1637 show that a single bulb sold for 3,000 to 4,200 guilders—equivalent to nearly 10 years' wages for a skilled craftsman. Some reports claim it was worth as much as a carriage full of goods. Another famous variety, Semper Augustus, was so rare that only two or three bulbs were known to exist, with one buyer supposedly offering 5 hectares (around 12 acres) of farmland for a single bulb.

However, such extreme trades were more myth than reality. Historian Anne Goldgar, who examined transaction ledgers and contracts, found only 37 cases where buyers paid more than 300 guilders (about a year’s wage for a master carpenter). This reveals that sky-high prices were rare exceptions. Most tulip trades were relatively affordable, and the speculative fever centered on only a few rare varieties. So yes, tulip prices did soar, but the notion that people were universally trading homes for bulbs is a massive exaggeration.

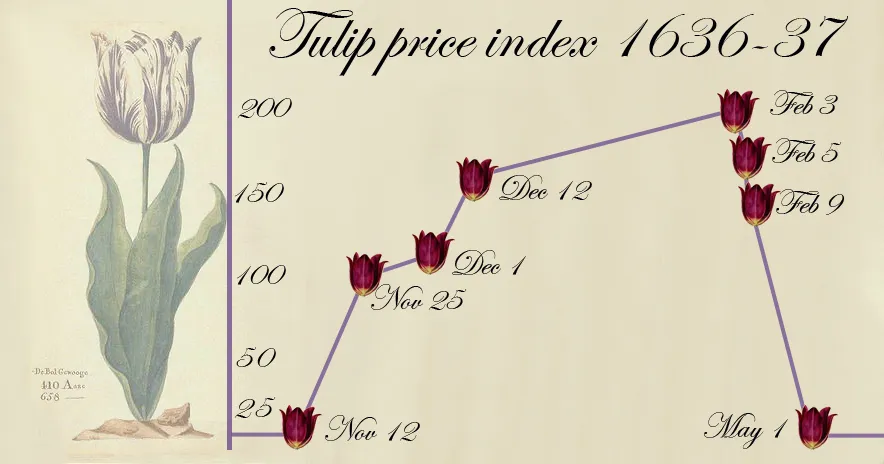

Tulip prices surged in late 1636 and peaked in early 1637 before collapsing rapidly. The chart below illustrates the price index for tulip bulb futures between November 1636 and May 1637.

The graph shows a steep rise during the winter of 1636, a peak in early February 1637, and a swift decline. While prices did crash, this did not devastate the Dutch economy. There were no widespread bankruptcies or financial system collapses, and trade and industry remained largely intact. Tulip trading was limited to a niche group—wealthy merchants, growers, and artisans—and had little direct impact on the general public.

Following the crash, there were some disputes and a temporary loss of trust among investors. However, the government and guilds introduced a solution: contracts could be voided by paying just 10% of the original value. This limited the fallout and prevented wider social unrest. In short, the economic impact was partial and contained, not the nationwide disaster many believe it to have been.

One of the most popular legends is that everyone from maids to merchants sold their property to speculate on tulips. 19th-century writer Charles Mackay famously claimed that "nobles, merchants, farmers, and even servants" were all caught up in tulip fever. Stories even tell of a sailor who mistook a rare bulb for an onion and ate it.

But many of these tales are fictional or wildly exaggerated. Satirical prints and gossip were common even during the mania, and many of the extreme stories were either jokes or later inventions. Modern historians agree that it was a speculative bubble involving only a minority, not a nation-wide hysteria. Anne Goldgar noted in her research that she could not find a single documented case of someone losing their home over tulips. Bankruptcies were rare, and most people exited the market without catastrophic losses.

This satirical painting by Hendrik Gerritsz. Pot, titled "Flora’s Wagon of Fools", shows the flower goddess Flora holding tulips as she leads a group of euphoric traders toward a cliff—symbolizing their coming downfall. Even back then, people mocked the frenzy. But over time, these satires were misinterpreted as factual accounts, inflating the myth that the whole country had lost its mind. In reality, tulip mania was a limited event and most of its famous anecdotes are more legend than truth.

Today, economists and historians take a more nuanced view of Tulip Mania. It is still recognized as the prototype of speculative bubbles, often referenced alongside the South Sea Bubble, the 1929 Crash, the Dot-Com Bubble, and recent crypto booms. The message remains: follow the herd, and you may get trampled.

However, some economists like Peter Garber argue that tulip prices weren’t entirely irrational. The rare striped varieties owed their appearance to the tulip mosaic virus, which was poorly understood at the time. With unpredictable traits and difficulty in reproduction, their valuation was understandably tricky. Furthermore, futures contracts were common in winter, when bulbs couldn’t be delivered, creating a pseudo-derivative market. So while speculative behavior existed, some price increases were driven by real uncertainty and imperfect knowledge.

Historian Anne Goldgar emphasizes the social and cultural consequences over the economic. The bigger problem wasn't just the price crash, but the loss of trust among friends and business partners, contract disputes, and community tension. But again, even these effects were short-lived and manageable. Her research helps debunk myths and presents a more accurate picture of what really happened.

The Dutch Tulip Mania is a fascinating case where myths and truths blend. While tulip prices did indeed soar and then crash, the idea that the entire nation was engulfed in madness is inaccurate. Many of the most dramatic tales were exaggerated or invented. In truth, it was a limited speculative bubble, with few participants suffering lasting harm.

Still, the lesson remains timeless. Whether it's tulips, tech stocks, or tokens, markets fueled by hype and herd behavior can end in pain. The real value of studying Tulip Mania lies not in laughing at the past, but in recognizing our own vulnerabilities in the present.